![]() First

Kentucky "Orphan" Brigade

First

Kentucky "Orphan" Brigade ![]()

A HISTORY OF

COMPANY F, FOURTH KENTUCKY VOLUNTEER INFANTRY, CSA

Geoffrey R. Walden

Written for the Green County, Kentucky, Historical Society

Part I: The Die Is Cast

As tensions began to tear the nation apart in the summer of 1861, the men of south-central Kentucky found themselves faced with an unwelcome decision: whether to support the North or South in the rapidly approaching Civil War. The Commonwealth attempted to retain its precarious hold on neutrality, and many worked to keep Kentucky out of this war. But the battle of Manassas, Virginia, on 21 July 1861 sealed the nation's fate, and many Green Countians made their decision as soon as they received word of the Southern victory.

The southern Kentucky economy was based on agriculture, mainly hemp, hay, and corn, and the region was thus tied firmly to the South. Slavery did exist in the area, but only the richest families worked their farms completely by slave labor, and most slave-holders owned only three or four field hands. Many Green Countians owned no slaves at all, but practiced the time-honored tradition of working their own farms. Clearly, the local men who joined the Confederate Army did so not to preserve slavery but to protect their constitutional right to determine their own laws and destinies.

The first Green Countians arrived at Camp Boone, Tennessee, on 1 August 1861. John Adair, the druggist in Greensburg, had served as Second Lieutenant of the Greensburg Guards, the local State Guard militia company. This unit reflected the division felt throughout Kentucky, since commander Edward Hobson eventually became a famous Federal cavalry leader, while most of the rest of the unit chose Southern sympathies. Adair brought ninety-two of these men south with him to Camp Boone.

Site of Camp Boone, Tennessee. The

house in the background,

"Idlewild," was on this site in 1861. (G. R. Walden)

These men from various backgrounds formed the nucleus of Company F, Fourth Kentucky Volunteer Infantry. Company F had members from Adair, Taylor, Wayne, and Hart Counties, as well as from Green, but from the beginning it was a Green County unit. Adair was elected Captain, with John Moore and John Barnett, both Greensburg businessmen, as Lieutenants. School teacher William L. Smith was elected Orderly Sergeant, and William B. Moore, son of the town jailer, was elected Second Sergeant. Allendale merchant Charles Cox was elected Fourth Sergeant.

Although most of the men in Company F were farmers or businessmen, other occupations were represented. Matt Champion, a young Irishman recently immigrated to Green County, was a stone mason. Ben B. Scott had just opened practice as town physician (he later became Assistant Surgeon of the Fourth Kentucky). Harley T. Smith worked as an overseer on his uncle's farm. Age also varied widely, although most of the men were in their early 20s. William Moore's brother Mark enlisted at the tender age of 12 and served as company drummer boy. John B. Scott from Taylor County was 45 when he enlisted.

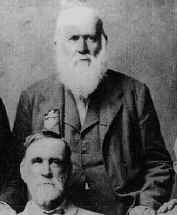

Dr. Ben B. Scott

from 1905 veterans reunion photo; copy courtesy Jeff McQueary

Capt. Adair had his company filled and organized in time to be mustered into Confederate service on 13 September 1861. Between then and November the men spent their time learning to be soldiers, with lots of drill and marching practice. This was a trying time for some of the men, unused to military life as they were, for their Major, Ben Monroe of Frankfort, was a demanding drill master. However, Maj. Monroe's attention to practice paid off at the battle of Shiloh, and camp life in Tennessee was more comfortable than ever again during the War.

The Kentuckians welcomed wholeheartedly the order to move north and occupy Bowling Green in November. Here the Fourth Kentucky formally became part of that celebrated command known to history as the Kentucky Orphan Brigade. Gen. John C. Breckinridge, perhaps the most famous Kentuckian of his time, took command of the Brigade and supervised its preparations for action. The men were issued some new Confederate gray uniforms and armed with old but serviceable smoothbore muskets.

Unfortunately, the first casualties in the company came not from action with the enemy but from disease. Measles ran rampant in the camps at Bowling Green, and many of the men fell victim to what was then a deadly disease. William Crumpton, Joseph Mays (Mayze), Frank Stubbs, and John B. White were among the Green County boys who gave their lives to their country before they ever saw the enemy. Some of these casualties were buried in the Old City Cemetery in Nashville, where they rest today.

Forced by the loss of Forts Henry and Donelson to fall back into Tennessee, the Confederate army made preparations to attack the Yankees in March 1862. U.S. Grant had rashly moved his army down the Tennessee River to Pittsburg Landing, and Confederate Gen. A.S. Johnston determined to strike him there. A slow march from Corinth, Mississippi, through mud and rain brought the army within striking distance on 5 April. The Kentuckians, proud possessors of brand-new British Enfield rifles issued two days before, made ready to attack the enemy near a small country church called Shiloh. Their baptism in fire on the next two days would earn them undying fame.

Part II: Company F "Sees the Elephant"

The Orphan Brigade, led by Colonel Trabue of the Fourth Kentucky, advanced into battle at Shiloh on the far left flank of the Confederate army on the morning of 6 April 1862. Other units had already surprised the Federal army, under General Grant, in their camps at dawn, and the men of Company F could hear the sound of guns off to their right. They were eager for the fray, and as they passed a group of John Hunt Morgan's soon-to-be-famous cavalry, who had already been in action that spring morning, they broke into cheers and struck up their favorite recruiting song:

Cheer, boys, cheer; we'll march away to battle,

Cheer, boys, cheer, for our sweethearts and our wives.

Cheer, boys, cheer; we'll nobly do our duty,

And give Kentucky our hearts, our arms, our lives!

Trabue advanced the Brigade across a small clearing and into a woodline, where he observed the Federals forming line across a stream bed. The regiments changed front to meet the enemy squarely (necessary by the tactics of the day), and in the process, the Yankees were ready first. The Fourth Kentucky found itself opposite the Forty-sixth Ohio Infantry, who fired a hasty volley over the heads of the Kentuckians. Now Major Monroe's long hours of drill paid off as the Fourth completed its maneuver and took careful aim at the Federals, only seventy yards away.

Monroe's drill field voice rang out with the commands "Fire by battalion! Ready, Aim, ... Fire!" The Kentuckians' volley was deadly, and the Ohio troops suffered their greatest losses of the day here (you can read about this action today on the monument of the Forty-sixth Ohio, erected on this spot on the battlefield). The Orphans kept their fire up, and soon the losses among the Ohioans were so severe that Monroe, seeing their lines waver, ordered a bayonet charge. With the shrill Rebel Yell streaming from their throats, the boys from Green County charged across the ravine and into the Federals, who broke and ran for the rear. Elated with their victory, the Orphans moved forward and through the abandoned Yankee camps. They had indeed "seen the elephant" (Civil War slang for going into combat for the first time), and had come out on top.

Marker on the Shiloh Battlefield

where the 4th Kentucky Infantry first went into action

Trabue moved the Brigade toward the right, searching for Federals to fight. While the Orphans were fighting on the left, the Confederates in the center had run into stiff opposition from Federals along a sunken wagon lane, later to be called the "Hornets Nest." Trabue brought his men against the back of the Hornets Nest, closing off the trap and capturing most of the Twelfth Iowa regiment. The Orphans saw little more action this day, and fell back to spend the night in the Yankee camps, enjoying the victors' spoils.

Not all the Green County boys were fortunate enough to make it through their first fight unscathed. Captain John Adair suffered a debilitating head wound, which would eventually force his resignation from service. James Barnett (a farmer before the War) was also badly wounded and died less than a month later. John Blakeman and Alexander Thompson were also wounded sometime during the day's action.

The Kentuckians were flushed with their victory of the sixth, but a different story awaited the Confederates on April 7. Grant's men had been severely punished, but their lines had held and they were reinforced throughout the night with fresh troops under General Buell. These fresh troops attacked with vigor in the morning, and the Confederates had no reserves to counter the thrust. As the Federal juggernaut moved against the tired and disorganized Confederates, the Fourth Kentucky was thrown in to plug a gap in the lines in the Duncan Field. Valiantly the Kentuckians charged again and again, holding their ground against Federals outnumbering them at least two-to-one. But the Orphans received no orders to fall back, so they stood to their task and suffered terribly for it. Henry Marshall, James Read, Jefferson Smith, young Irishman Matt Champion, and Milton Blakeman were all killed. They are probably buried in one of the mass Confederate graves on the battlefield. (Milton was John Blakeman's first cousin, and John would later name his first son after Milton.) Harley Smith (a 21-year-old ex-overseer) and John Moore (ex-Greensburg grocer) were wounded, and Charles Cox was wounded and captured (he later took the oath of allegiance to the Federals). Despite their losses, the Fourth Kentucky yielded little ground, until ordered to fall back late in the afternoon.

Mass grave on the Shiloh Battlefield, near

where the

Orphan Brigade fought (G. R. Walden)

As the Confederates retreated to Corinth, Mississippi, the Orphans were afforded little rest, as they formed the army's rear guard. When they finally reached the safety of the lines at Corinth and took stock of their situation, many were appalled. The Fourth Kentucky had lost forty-nine percent casualties, among the highest of any Confederate unit at Shiloh. Company F suffered forty-one percent casualties. These losses could never be fully made up, and gave truth to the old saying that "the South never smiled again after Shiloh."

The Orphans didn't spend long at Corinth, as their services were needed to bolster the Southern troops at Vicksburg. So they left their comrades in Corinth (including William Darnell of Company F, who died of disease on 25 May 1862) and marched south. At Vicksburg they performed lots of picket duty, watching ironclad warships battle each other on the Mississippi. Breckinridge took his force to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in August to recapture that city from the Federals. The Orphans drove the Yankees back to the river, but help from the Confederate Navy failed to materialize, and the Kentuckians fell back from the fire of the Federal gunboats. Losses were light, with none in Company F. However, non-combat losses continued to whittle down the ranks of Company F, as Daniel Rucker transferred to the Third Kentucky in May, Winston Anderson died of disease in August, Adair Waggoner was lost to disease in mid-September, and William L. Smith was discharged due to illness in September. In common with most Civil War units, Company F lost far more to disease than to enemy bullets.

The Kentuckians almost got the longed-for opportunity to visit their homes when Breckinridge was ordered to reinforce General Bragg in his great autumn invasion of Kentucky. However, transportation problems plagued the Orphans, and Bragg was defeated at Perryville before they could reach him. On the road north of Knoxville, only 20 miles from Cumberland Gap and home soil, the boys from Green County received orders to turn around and return to Murfreesboro.

Here the Orphans spent a pleasant late fall of 1862. New uniforms were issued to replace those worn out on the summer's hard campaigning through Mississippi and Louisiana, and visitors from home brought welcome news and packages. However, not all the men were content. Nineteen-year-old Joseph Thompson was listed as having deserted on November 3. Perhaps this young man had had enough of war, or perhaps he received word from home that his presence was needed. In any case, his service with Company F ended here. Also severing ties with Company F was sometime-surgeon Ben B. Scott, who was discharged due to disability on November 15.

When Bragg determined to conduct a rare winter campaign and attack the Federals near Murfreesboro on the last day of 1862, the Orphans remained in reserve, watching the action from across Stones River. His hard-charging troops having pushed the Yankees back over a mile, Bragg was sure the enemy would retreat to Nashville. But both sides held their ground, waiting out New Years Day 1863 to see what the other would do.

In a bold move calculated to turn his enemy's left flank, Bragg ordered Breckinridge to attack and seize the high ground to his front on January 2. Having carefully reconnoitered the area, Breckinridge knew such a charge would be suicidal: the Federals had massed over fifty cannon on a hill across the river. He pleaded with Bragg to withdraw his orders, but Bragg was adamant. Breckinridge had no choice but to order his men to the assault, the Orphans in the front rank closest to the enemy guns.

The assault quickly achieved initial success, as the Southerners fired a volley at close range and charged with the bayonet, driving the Yankees from the ridge. However, they did not stop, but pursued the fleeing foe toward the river. This placed them squarely in range of the massed guns, which wrecked havoc in their ranks from bursting shrapnel and shells. The Orphan Brigade commander, General Hanson, was mortally wounded. The Fourth Kentucky lost two color-bearers, and the Sixth Kentucky, three. Men fell all along the line. Although some of the Confederates actually crossed the river, the main force could not withstand the terrible fire, and they fell back to the starting point. The Orphan Brigade had lost nearly a third of its men, and when Breckinridge saw the pitiful remnant, he wept for his "poor Orphans" who had been "cut to pieces."

Major-General John C. Breckinridge

In spite of the overall Brigade losses, Company F was fortunate in the battle of Murfreesboro, losing only one captured and four wounded. Lt. John Moore, who had also been wounded at Shiloh, and Pvt. M. L. Davis of Green County were among the latter. Daniel Blakeman was mortally wounded and captured, and died later in a Federal hospital. Bragg pulled his army back toward Chattanooga, and the Orphans spent the spring refitting and reorganizing.

Part III: The Fourth's Finest Hour

After decimating Breckinridge's Division, particularly the Kentuckians of the "Orphan" Brigade, in the disastrous charge at Murfreesboro on the second day of 1863, Gen. Bragg pulled his army back into south-central Tennessee. Here, around Tullahoma, Manchester, and Wartrace, the Army of Tennessee went into camp, lightly manning defensive positions in case the Federals decided to move forward from Murfreesboro. The Green County boys of the Fourth Kentucky camped near Manchester, and enjoyed a period of relative relaxation, drilling and rebuilding their depleted ranks.

John Blakeman's brother Daniel, who had just joined the army four months before, died in a hospital near Murfreesboro, while a prisoner of the Federals in January 1863. There is some debate on the exact manner of his death: the brigade historian says he died of disease, but his official service record shows that he died of a gunshot wound. Perhaps he felt well enough to participate in the battle, but received a mortal wound on 2 January.

John B. Moore was promoted to Captain on 12 February, replacing John Adair, who was disabled by his wound at Shiloh. John Barnett was promoted to First Lieutenant on the same day. Company F remained firmly in Green County hands.

A few of the Green Countians participated in a little action in March and April, guarding some government supplies and building a bridge near McMinnville. These men of the McMinnville Guard, including Sgt. William Moore and Pvt. John Blakeman of Greensburg, were overrun by Federal cavalry and John Blakeman was captured. Fortunately, he spent only a month in captivity, arriving back with Company F in time to march in a parade that decided the unofficial drill champions of the Army of Tennessee.

This drill competition was the highlight of the spring for the Orphans, and it clinched their reputation for excellence. Each of the Kentucky regiments competed against a regiment from Gen. Adams' Louisiana Brigade, the Fourth Kentucky beating the Nineteenth Louisiana on 21 May. Each of the Orphan regiments handily defeated its rival, until the Ninth Kentucky was slated to compete on 22 May. Unfortunately, marching orders for the Orphan Brigade arrived on that day, and the competition was never finished. However, there was no doubt in the Kentuckians' minds who the drill champions were.

As he had the previous summer, Breckinridge took his division to Mississippi, this time to help relieve the siege of Vicksburg. However, the reinforcements were too late to save the city, which surrendered on the Fourth of July. The Confederates fell back to Jackson, where they were attacked by Gen. Sherman in mid-July. The Fourth Kentucky was not heavily engaged, and Company F lost no casualties. But disease continued to thin the ranks of the Green Countians as W.W. Woodring was discharged due to disability in May, and Martin L. Davis died of disease in September.

While the Orphans were in Mississippi, Bragg was forced out of middle Tennessee, and he surrendered Chattanooga to the enemy. The Federals grew overconfident and separated their forces in north Georgia. Unusually bold and decisive, Bragg determined to strike the Yankees before they could consolidate their forces. He struck them along a sluggish creek called Chickamauga on 19 September.

The ensuing battle was the largest and bloodiest of the war in the western theater. The lines see-sawed on the nineteenth, neither side gaining a distinct advantage. Bragg ordered Gen. Polk to assault the Yankee lines at dawn on the twentieth, while Gen. Longstreet, sent from the Army of Northern Virginia to support Bragg, was to attack in the center.

Various misunderstandings delayed the dawn assault, but Breckinridge ordered the attack at 9:00 a.m. The Orphans charged forward, filling the woods with the wild Rebel yell. They struck the Federal works at an angle, at a place marked today in Chickamauga National Military Park by a painting showing their attack. The Fourth and Sixth regiments, being on the right of the Orphans' line, passed by the log defenses and met their enemy in the open. In the area of the Kentucky Monument in the park, the Fourth Kentucky emerged from the woods and charged the Federal Fifteenth Kentucky, routing them and capturing two cannons of Bridges' Illinois Battery. It was one of the Fourth's finest hours, as the men joyfully jumped astride their captured prizes and turned them on the fleeing enemy.

Kentucky Monument at Chickamauga

(photo by G. R. Walden)

Tragically, the attack did not go as well for the rest of the Orphans. The Yankee defenses were too strong for the left of the brigade, which was fearfully cut up in three bloody assaults. Gen. Helm of Elizabethtown, commanding the brigade, was mortally wounded. Col. Lewis of the Sixth Kentucky assumed command and pulled his men back to rest them and reorganize the shattered command. The brunt of the remainder of the battle was fought by other units, notably Longstreet's Corps which split the Federal center and sent the Federal right fleeing toward Chattanooga. The Federal left held firm under Gen. Thomas (who earned the nickname "Rock of Chickamauga" this day), finally retreating after dark.

Because they were on the right and avoided Federal works, the Fourth Kentucky suffered few casualties at Chickamauga, Company F having three killed and one wounded - Fielding Skaggs lost his left hand, and was named to the Confederate Roll of Honor. Bragg slowly pursued the beaten Yankees to Chattanooga, where he foolishly tried to surround and besiege them.

Gen. Grant bided his time, carefully building up the Federal forces until he had enough men to force Bragg from Lookout Mountain at the end of November. The next day the Yankees assaulted the Confederates on Missionary Ridge, breaking their center and routing them toward Georgia. The Orphans were. stationed on the right of the line under Gen. Pat Cleburne, where they stood firm until nightfall, covering the army's retreat after dark. The Fourth Kentucky spent the battle in reserve, suffering no casualties.

Bragg's shattered army retreated to Dalton, Georgia, where they set up winter quarters. Bragg, never popular with his generals and downright hated by many of his men, was finally replaced by Gen. Joe Johnston, who spent the winter rebuilding his army. The Kentuckians were camped near a spring house on the Western & Atlantic Railroad (a Georgia historical marker at the Hamilton House in Dalton marks the spot today). Here they enjoyed a comparatively relaxing winter, with plenty of clothing and equipment issues to replace those worn out during the previous summer's hard service. They engaged in army level drills and mock battles, and the Fourth Kentucky formed a Glee Club to entertain the local civilians. The Orphan Brigade, now under newly-promoted Gen. Lewis, participated in an army-wide snowball battle on 22 March, which broke the monotony of camp life (and also broke a few bones when some soldiers put rocks in their snowballs!)

Hamilton Spring House, Dalton, Georgia

Orphan Brigade headquarters were located here in the winter of 1863-64

(photo by G. R. Walden)

The army rebuilt its morale over the winter and spring, but the Kentuckians could not rebuild their ranks. Company F now had only about 25 men, a shadow of its former strength. Losses continued to chip away at the total, as William Wilson of Green County died from disease in February 1864. In April, 15-year-old drummer Mark Moore was discharged. Having fought in all the battles up till now, he was classified as underage by the recent conscript law and was sent home.

The Fourth Kentucky continued to lose battle casualties, some under bizarre circumstances. Dalton is guarded to the west by Rocky Face Ridge, a mountainous chain of ridges with nearly perpendicular faces fronting the Federals. In February, the Fourth was stationed on Rocky Face as a human telegraph line, stretching from the top back down into the valley. One morning Englishman George Disney of Company K was arising from his blankets, when he fell back down and appeared to go back to sleep. When his comrades tried to rouse him, they found that he had been hit by a random bullet, which entered his mouth as he yawned and killed him instantly. There is a Georgia historical marker today at the foot of Rocky Face just outside Dalton, honoring George Disney, whose grave can still be seen on top of Rocky Face.

As the army prepared for the upcoming campaign, a unique unit was formed. Gen. Breckinridge presented his old brigade with eleven special British long-range target rifles. These were given in turn to the best marksmen in the brigade, who became the Kentucky Brigade Sharpshooters. Lt. George Hector Burton of Company F was chosen to lead this elite group, which was exempt from normal guard duties. They spent their time trying out their new weapons, which were accurate at a half-mile. By the end of April, they were ready to meet the Federals in the campaign that would decimate the Orphan Brigade as an effective fighting force and decide the fate of the South.

Lt. George Hector Burton

cdv in author's collection

Part IV: The Atlanta Campaign of 1864

The campaign started for the Orphans on May 7, as they left their winter camps and took their old positions on Rocky Face Ridge, opposing General Sherman's huge Federal army The Orphans helped repulse Sherman's advances against Rocky Face, then retreated with the Southern army to Resaca. The remainder of the campaign to Atlanta consisted of constant skirmishing and sharpshooter fire, never out of range of the enemy and usually in cramped trenches. Life in the Atlanta Campaign was a preview of the terrible trench warfare to come in World War l.

General Johnston moved his army ever closer to Atlanta, countering Sherman's flanking movements. The Green Countians fought in large battles and small. Company F took 23 percent casualties at Resaca in May, including young Alex Thompson, who was wounded in the ankle. The Kentuckians fought at Dallas, near New Hope Church, where the Orphans made an unsupported charge against entrenched Yankees and suffered their highest casualty rate of the War (51 percent). The army spent almost a month in the front lines defending Kennesaw Mountain, and Harley T. Smith was captured in a skirmish there on June 20. Edward Dobson was wounded the next day at Pine Mountain. Company F's strength continued to dwindle.

General Johnston eventually retreated all the way to Atlanta, and was replaced by General Hood, whom it was thought would drive the Yankees back. Hood was an impetuous and reckless fighter, and he wasted his army's strength in futile assaults against the Yankees outside Atlanta. The Orphans fought in the battles of Peachtree Creek and Atlanta (which they called Intrenchment Creek) in July, and at Utoy Creek in August. Casualty rates among Company F were not high during these battles, and the only Green County casualty was Luther Hatcher, who was captured on July 22 at Intrenchment Creek.

The end of August 1864 found the Orphans guarding the important rail center at Jonesboro, south of Atlanta. Sherman, determined to crush Hood, had moved most of his army around Atlanta's strong defenses, and, unknown to Hood, had concentrated near Jonesboro. Only General Hardee's Confederate Corps stood in their way. An attack was ordered to stall the Federal advance on August 31, and the Orphans as usual were in the forefront. They launched their assault at full speed, but the Yankees were strongly entrenched, and a deep ravine, unseen until too late, lay between the Kentuckians and the enemy lines.

Enemy fire tore at the Southern ranks, dropping men all along the line. Here the faithful color-bearer of the Fourth Kentucky, Robert Lindsay of Scott County, who had borne the battle flag in every battle of the War, took a mortal wound in the chest. Father Emmeran Bliemel, part-time chaplain of the Fourth Kentucky, was killed as he knelt behind the charging lines to offer Absolution to a dying officer. He was the first Catholic chaplain to be killed in battle in an American war. The Federal fire and the deep ravine proved to be insurmountable, and the attack failed.

The next day, September 1, 1864, found Hardee's Corps bravely facing over two-thirds of the entire Yankee army. The Southern soldiers, worn out by constant fighting for nearly four months and heavy battle losses, nevertheless manned the lines, determined to save Atlanta from the Federals. But they were spread so thin that instead of the usual unbroken battle line facing the enemy, the men were placed in the trenches with a yard or two of open space between each man. Grimly the men of the Orphan Brigade, now down to about 800 men (barely the strength of one regiment in 1861), watched parts of two Yankee divisions deploy in their front and ready themselves for the attack.

In spite of the overwhelming numbers facing them, the Orphans threw back the first assault. But then the entire Federal force charged, and the brigade to the Orphans' left was forced to give way. The Kentuckians held their own lines, fiercely battling the Yankees to their front, but they were soon surrounded by Federals pouring though the gap to their left, and they found themselves fighting for their lives with Federals on three sides. The left of the Brigade was overwhelmed, and many men of the Second, Sixth, and Ninth regiments were captured. It was here that the torn and bullet-riddled battle flag of the Sixth Kentucky, which can be seen today in the Kentucky Military Museum in Frankfort, was captured. The men of the Second Kentucky tore their battle flag to pieces to save it from the same fate.

To save themselves from complete annihilation, the rest of the Brigade fell back a few hundred yards, guarding the army's rear and the remnants of the units that had been overwhelmed. The Orphans held this new line with such tenacity that the Yankees were fooled into thinking they had struck a fresh force, and they broke off the assault, allowing Hardee time to gather his forces and abandon Jonesboro, falling hack to the south. As they had so many times before, the Orphans guarded the retreating army's rear. The next day, Hood abandoned Atlanta, and Sherman's long campaign to capture the "Gate City" of the South was over.

The battle of Jonesboro marked the end of the Orphan Brigade as an effective infantry force. Unable to recruit effectively at home throughout the War, the Orphans watched their ranks dwindle away from combat and sickness losses. The grueling Atlanta Campaign reduced the Brigade by over one-half, and only some 500 men answered the roll call on September 4.

However, all was not lost for the Orphans, as they received orders to proceed to Griffin, Georgia, and convert to mounted infantry. Throughout the War, many of the Kentuckians had dreamed of converting to cavalry and joining General Morgan or Forrest to fight on their home soil. At last, it seemed their dream might come true.

Part V: The End of an Era

We left the "Orphans" of the Kentucky Brigade fighting for their lives at the battle of Jonesboro in September 1864. Those who managed to avoid capture fell back to Griffin, Georgia, where they finally realized their long-held wish to convert to mounted infantry. As the front line moved farther and farther from their homes, the Kentuckians recognized that the only way they would realistically return to fight on home soil was on horseback. They felt they could renew Southern feelings in their home state and gain recruits to fill their depleted ranks by invading Kentucky in raids, reminiscent of the famed cavalry raider John Hunt Morgan.

Marker to the Orphan Brigade in Griffin,

Georgia

(photo by G. R. Walden)

The transition to "critter-back" was not without its mishaps. The men were mounted mostly on captured Yankee horses, and there were never enough to go around. Many of the Orphans had to make do with mules, and a good number never found mounts. Although most of the Kentuckians were quite familiar with the equestrian skills, they still had to learn the approved cavalry drill and tactics, and such basic mounted service supplies as saddles and saddle blankets were always in short supply.

In contrast to their former service full of heavy fighting, the Orphans spent the final months of the War in a relative backwater. Their dream of returning to Kentucky never materialized, as they were needed too badly elsewhere. Gen. Sherman was about to begin his famous March to the Sea, and the Kentuckians were picked to try to stop him.

This was a hopeless task, as the Confederates were never able to mount even a portion of the force necessary to confront Sherman on equal terms. Nevertheless, the Orphans and other mounted units performed valuable service by skirmishing constantly on the flanks and rear of the Yankee host as it moved through Georgia, holding in check much of the potential rampage and destruction of Sherman's marauding "bummers." The Orphans first met Sherman in mid-November 1864 at Stockbridge, Georgia, and succeeded in delaying one of his Army Corps. During this period Ambrose J. Hall of Taylor County was promoted to 3rd Sergeant of Company F, to replace Richard Bowling who was killed at Jonesboro.

3rd Sgt. A. J. Hall

from a 1905 veterans reunion photo; copy courtesy Jeff McQueary

The Orphans followed Sherman to Savannah, then moved to the area of Augusta in early 1865. Their fighting spirit undiminished, they met in February to draft a remarkable set of resolutions, in which they renewed their pledge to uphold the Confederate government until the end They requested that these resolutions be published in newspapers across the South, and they suggested that disloyal editors should join them in the ranks to experience firsthand how their Cause ought to be supported.

Although the entire Brigade never returned to Kentucky, a number of the officers and sergeants were released from duty at this time to return home and attempt to recruit. Such action, necessarily conducted behind enemy lines, was full of danger, and some of these recruiters were killed by the Federal Home Guards. Lt. John Barnett of Greensburg was assigned to recruit for Company F, but he managed to perform his duty unscathed.

Amid the disintegration of the South, the Orphans continued to protect their assigned territory against the Yankees to the bitter end. Their last battle came on 29 April 1865, nearly three weeks after Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia. On this day a portion of the Fourth Kentucky Infantry fought one of the last organized actions east of the Mississippi River, as they skirmished with a Federal force near Stateburg, South Carolina. Here Company F suffered its last battle casualty when Corp James W. Nelson of Adair County was wounded.

Their resolute determination could not save the Orphans from the fate of the Confederacy, and they were ordered to march to Washington, Georgia, and surrender their arms. On 6-7 May 1865 the story of the Orphan Brigade came to an end as the men fell in for the last time, proudly dressed their ranks and formed roll call, then turned over their trusty Enfield rifles and accepted their paroles from the Federal authorities. Company F had been reduced by casualties to a mere 19 men, including two temporarily serving from other companies. The original parole muster roll, now in the Iowa State Historical Society, shows the following members of Company F surrendered at Washington:

Capt. John B. Moore

1st Lt. William Ambrose Smith

1st Sgt. George Edwards Johnston

Sgt. William B. Moore

Sgt. James William Castillo

Corp. Edward P. Rudd

Corp. Joseph Nickols

Pvt. Joseph Alexander Atkins (Musician)

John T. Blakeman

James G. Bryant

Edward W. Hickman (native of Georgia)

Thomas L. Kelly

Richard B. Marshall

Samuel Marshall

Robert R. Peebles

Daniel Lunksford Smith

James Tittle (native of South Carolina)

James Loope (attached - not from Co. F)

George Wells (attached - not from Co. F)

Original Parole of Pvt. Daniel L. Smith

Collection of Jacob Hiestand House Museum, Campbellsville, KY

(courtesy Steve Menefee)

The long War was over. The former members of Company F traveled the long road home, most taking the Oath of Allegiance to the Federal Government as they passed through Nashville. Most of the men arrived home, after being absent for nearly four years, late in May 1865 to take up their lives where they had left off in 1861. The following short compilation shows what became of some of the men of Company F after the War.

Of the Green Co. boys, John A. Adair died in Hart Co. on 28 November 1898, and is buried on family land near Canmer. John B. Moore committed suicide in Greensburg on 17 May 1877, and is buried in the city cemetery. John Barnett died on 18 January 1915 and is buried in the Barnett-Marshall Cemetery off Hwy. 61 north of Greensburg (Dr. B. T. Marshall, who died of an accidental gunshot wound on 22 May 1875, is also buried there). William L. Smith moved to Dallas County, Alabama, where he died in 1866. His widow married William A. Smith, who had moved to Dixie, Alabama, where he became a tax collector and died on 23 April 1897.

John Blakeman returned to his father's farm, where he married and raised a family. He died on 7 October 1884 and is buried in the family cemetery in Cox's Bend east of Greensburg. Charles Cox, who had taken the Oath of Allegiance after Shiloh, moved to Taylor Co., where he died on 18 April 1913. He is buried in the Brookside Cemetery in Campbellsville.

The Marshall brothers, Richard and Samuel, moved to Texas following the War. Samuel lived in Grayson Co., near Kentucky Town, which had been founded by a group of Green Co. immigrants around 1854. He died on 4 November 1911 and is buried in Oak Hill Cemetery near Whitewright. Young Mark O. Moore, just sixteen years old when the War ended, found his way to Mississippi, where he eventually got into trouble. After assaulting a young lady he was hanged by a lynch mob in Wahalak, Mississippi, in June 1884.

Daniel Lunksford Smith was the last Confederate soldier living in Green County when he died on 19 September 1931. He is buried in the Howell Cemetery in Allendale. Dr. Ben B. Scott died in Greensburg on 16 January 1908 and is buried in the city cemetery. Fielding Skaggs, who was named to the Roll of Honor after Chickamauga, was murdered in an altercation in Green County in 1886. Harley Thomas Smith was another Orphan who sought his fortune elsewhere. He moved his family by covered wagon through Kansas to Oklahoma, where he became Justice of the Peace in Pottawatomie County He died on 11 April 1919 and is buried in McLoud, Oklahoma. Alex Thompson never quite got the War out of his system. He remained friends with George Johnston, and they doubtless enjoyed many hours reliving their war experiences. Alex died 7 July 1930 and is buried in the Perkins Cemetery west of Bloyd's Crossing.

George Hector Burton of Columbia moved to South Carolina, where he became one of the most popular Baptist ministers in the area. Despondent over failing health, he committed suicide on 2 February 1922 and is buried in the cemetery of his parish church near McCormick, SC. Adair Countian Joseph Atkins died in Louisville on 6 August 1908 and is buried in Lebanon. James G. Bryant worked in the Adair Co. courthouse for many years and died on 1 August 1920. He is buried in the Loy Cemetery near Gadberry. James W. Nelson spent his last years in the Confederate Soldiers Home in Pewee Valley, where he died on 22 May 1907. Andrew Knox Russell moved to Marion Co., where he served as Sheriff. He died on 1 April 1914 and is buried in Lebanon.

Many of the Taylor County natives led full lives after the War. George Johnston farmed and served as sheriff before moving to Oldham Co., where he died on 1 July 1930. He is buried there in the Floydsburg Cemetery. Despite the loss of an arm in battle, Theodore Cowherd served in the Louisville Public Works until his death on 14 September 1920. He is buried in Cave Hill Cemetery. A. J. Hall moved to Green Co. after the War. He died on 26 June 1916 and is buried near Eve. Jesse Johnson died in Colsby on 30 March 1912 and is buried in Brookside Cemetery in Campbellsville. James W. Castillo returned to his native Wayne Co. and became a successful doctor. He died on 1 September 1895 and is buried outside Monticello. Andrew Jack Russell removed to Glasgow after the War, where he died on 18 October 1912. He is buried in the Glasgow Cemetery, in the shadow of Fort Williams, built by the Federal army in 1863.

Click here to see a detailed roster of Company F, Fourth Kentucky Infantry.

Copyright � 1989-1991, 1998, Geoffrey R. Walden; all rights reserved. This article originally appeared as a serial in the "Green County Review," journal of the Green County Historical Society, Vol. 12, No. 4 (Summer 1989), pp. 52-57; Vol. 13, No. 2 (Winter 1990), pp. 24-26; Vol. 13, No. 3 (Spring 1990), pp. 48-49; Vol. 14, No. 2 (Winter 1991), pp. 20-21; Vol. 14, No. 4 (Summer 1991), pp. 51-53.

![]() Return

to History Page

Return

to History Page

![]() Return

to Roster of Co. F, 4th Ky. Inf.

Return

to Roster of Co. F, 4th Ky. Inf.

![]() Return

to Orphan Brigade Homepage

Return

to Orphan Brigade Homepage

URL: https://sites.rootsweb.com/~orphanhm/cof4kyhist.htm